by Colonel Tom Moe, U.S. Air Force (Retired)

I returned to the United States from Vietnam during Operation Homecoming with a large group of prisoners of war (POWs) on March 14, 1973. We had figured out that the release was taking place when a few weeks earlier, a C-141 flew low over our camp — and no one was firing at it!

The day before our release, we were told by the camp commander that we would be freed the next day. Because of the C-141 sighting, we tended to believe him even though over the years, we had often optimistically (but incorrectly) forecast our release. So, on that day, we were all mustered in a group (which had never happened before), and the camp commander, with a translator beside him, read the document describing the agreement of our release. Then the commander said that we could all go back to our cells and clean them up. That wasn’t going to happen (and didn’t). Instead, one of our mates, Bud Day (later a Medal of Honor recipient), strolled forward and said to the camp commander, “In some minutes,” and then walked off. Over the years, if we had ever asked for anything from the guards like a new bar of soap or whatever, their answer had always been, “In some minutes.” That meant anything from a few minutes to never. In this case, Bud meant “Never.” Love it!

We went back to our cells to await the next day. Sleep time was signaled by a guard banging on a large gun shell or gong, and that night was no different. I remember so clearly my absolute absence of excitement for the coming day that I fell instantly asleep on my wooden “bed.” After five-plus years in prison (for me, and up to nine years for Ev Alvarez), our emotional level was pretty much zero.

The next morning, we were awakened as always by the “gong,” and went about getting up and waiting for our morning “soup” (watery vegetables of questionable origin) and a chunk of tasteless bread. Later in the morning, we could see that tables were set up with clothing for us, and the media began to arrive including Walter Cronkite. When any of the newsmen approached us, we would turn our backs on them, including Cronkite. Virtually all of us felt that the media had betrayed us, not by reporting the war, but by only telling one side of the story. Bad things happen in warfare, but the media never told of atrocities by the Communists or they downplayed it by excusing them. The media never sensed the irony that there was no such thing as a free press in the Communist world (Viet Cong or otherwise), so the media never had access to what was going on in our enemy’s world. I won’t digress.

Finally, the media gave up, especially when a cameraman tried to follow one of the POWs into his cell to take photos. The POW attacked him, took his camera and smashed it on the ground so that it broke into pieces, the flash bulb going off in the process. The camp commander raced to the cell and would have had the POW beaten even to death had this happened during the war, but he stopped in his tracks as he saw the media stepping forward to take note of what might happen. Nothing came of it.

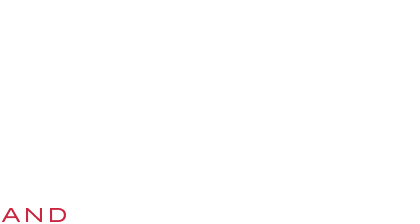

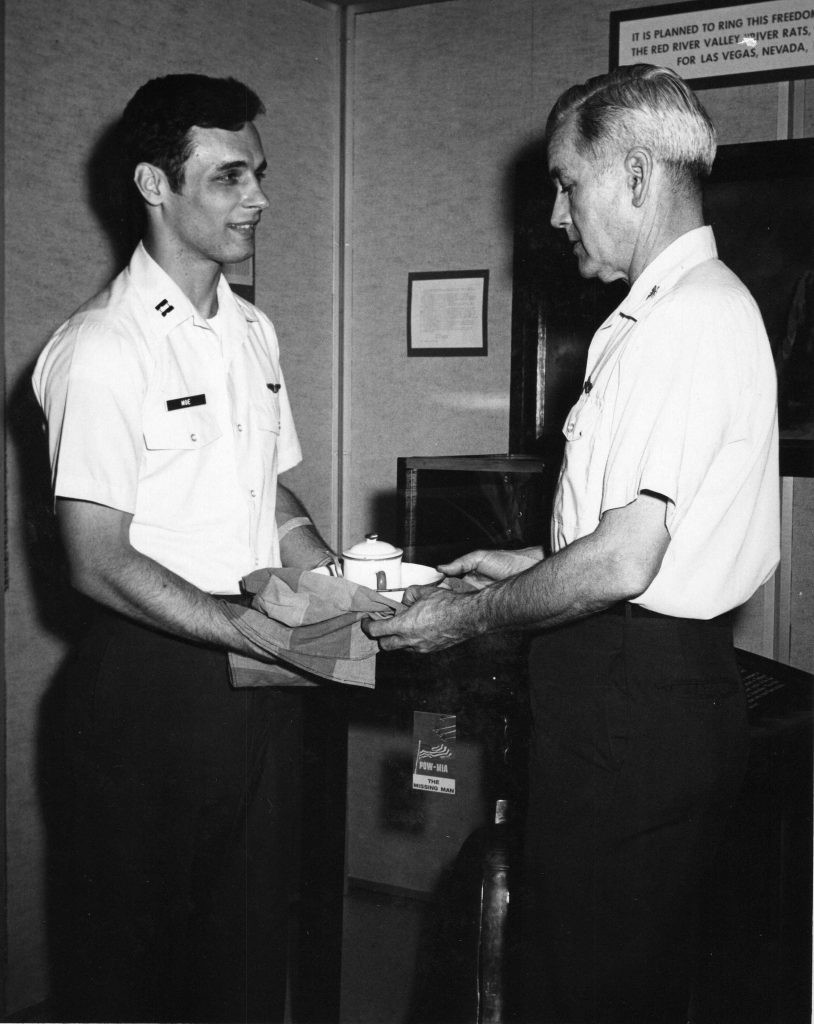

Then we lined up and picked up our go-home clothes from the tables. We were told that we could bring some things home like our cup and pajamas and some of us did. Everything I brought home, I did so to give to the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force as soon as I got to the Wright Patterson hospital in Dayton, Ohio.

Then we loaded up in buses — no blindfolds, no handcuffs, no leg irons — and drove off to near Gia Lam Airport. We stopped among some warehouses where the Communists had laid out beer and bananas for us. We stood there and didn’t touch a thing. We were loaded up in the buses again and driven to our release point at Gia Lam Airport.

We exited the buses, lined up and kept our serious demeanor. No smiles. No one had given any instructions for us, but no one needed to. We had often lived in isolation in the POW camps (for me nine months and more, for others a matter of years), but our training and discipline was so effective, we functioned with dignity and honor without any contact with others. This is a tremendous source of pride for us and our love of country.

As our names were called off by one of the officers who had directed torture on us in the past. In one instance, the torture was so severe that the doctors, upon examination when I returned, said I should not have survived the internal damage done by the beating and kicking–not to mention surviving drowning due to what we now call “water boarding.” We stepped forward to an American officer who escorted us one-by-one to the awaiting C-141s. I believe there were three of them that day.

When the last POW was on board, we taxied out and took off. Some of my mates say that we cheered when we left the ground, but my memory is that we were silent until the pilot announced that we were “feet wet” (a pilot’s term meaning “over the water”). Then we cheered with great gusto and maybe shed a tear or two.

We settled in for the flight to Clark Air Base in the Philippines. During the flight, we were treated to cigarettes and cigars and the latest Playboy Magazines. We were quite surprised at how the centerfold photos left nothing to the imagination. That was one of our first clues that LOTS had changed back home over the years. Often, after I had returned home, I might say or ask something that would prompt someone to ask, “Where have YOU been?” Obviously, not knowing about my sabbatical in Vietnam, my answer was always, “I guess I was tied up.”

When we landed at Clark, Navy Admiral Noel Gayler was waiting for us to disembark, which we did one by one as our names were read, to the huge crowd that gathered to welcome us to freedom. The release was, of course, broadcast around the U.S. and perhaps to an even wider audience, so I learned that my wife, parents and family could witness our arrival.

We were driven to the hospital at Clark to begin our recovery, take a warm shower, EAT good food, get uniforms and prepare to return to America.

Food. The earlier groups to be released were treated to bland food for their first meal. The doctors thought that their systems couldn’t take rich food. After a not-so-minor revolt (they were ex-cons after all), the meals were changed to real food. So, by the time I was released, we were presented with a wide array of great food: steak, lobster, you name it. As I stood in line at the hospital restaurant, a staffer asked me if I wanted anything to eat before I got to the trays. I asked for an apple. I had craved an apple for over five years. Then as we approached the trays, we were confronted with an ice-cream bar. I made a huge dish of ice cream and bananas and had it finished by the time I got to the trays. Then I piled my tray full of food and ate very bit. No problem, and I knew of none of my mates who had any problem eating like, well… pigs. And loving it.

Before we turned in, we gathered in a meeting room and formed a choir. One of the guys directed us in a couple of hymns and patriotic songs. I believe there are films of this somewhere.

Then we “turned in.” But I couldn’t sleep. I remained awake for three days. At night, I would sit in an easy chair by the hospital window and look out over the base. I was almost overwhelmed by being able to see for some distance, since for so many years, my visual world often didn’t extend for more than a few feet, except for the occasions when we walked to an interrogation or to wash.