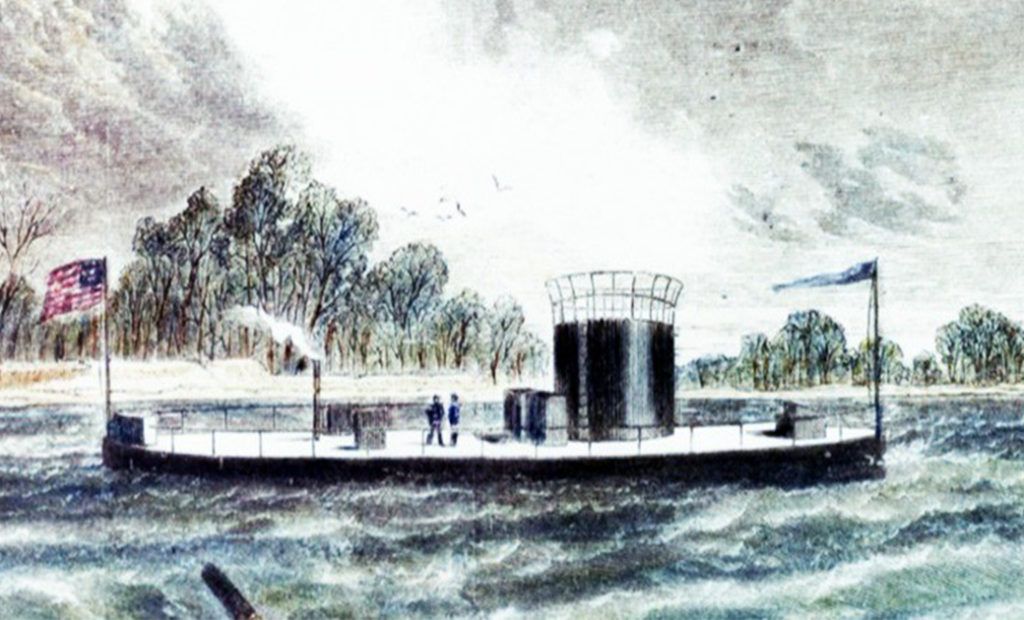

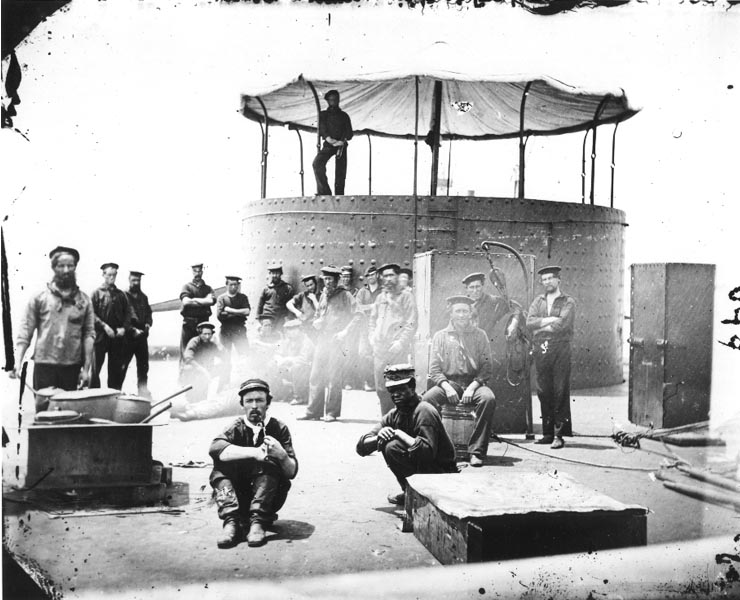

Siah Hulett Carter, given name Josiah Hulett, was born and grew up as a slave on the Shirley Plantation in Charles City, Virginia. The plantation was owned by Hill Carter, a Confederate Army Colonel during the war who would try to instill fear into his slaves with stories that any slaves who tried to escape to Union ships would have a piece of iron tied to their necks and be thrown overboard by the North’s sailors. Siah, correctly, ignored this story from his master and on May 18, 1862 escaped and paddled out to the USS Monitor. We are lucky that the Monitor’s Acting Paymaster, William Keeler, was a highly active letter writer to his wife. Keeler recorded the night that Siah came aboard, writing about the “poor trembling contraband” that rowed a boat out to them in the night, causing a warning shot and call to stations as the crew thought it was a Confederate boarding party. “O’ Lor’ Messa, oh don’t shoot, I’se a black man man Massa, I’se a black man,” Siah called out to them, Keeler wrote. Siah would be allowed to enlist at the rate of Ship’s Boy the next day and would assist the cook with his duties.

At this point in the war, the Fugitive Slave Act was still technically in effect, which required runaway slaves to have been returned to their masters if found. The Union military had no policy on the matter, but early in the war many slaves were often returned to their bondage. Some generals, such as General Benjamin Butler, refused to do so on the grounds that if the Confederates wanted to consider people property, then they would be confiscated as contraband of war and set free to hurt the Confederacies work force. Thus, the term contraband for escaped slaves was born. Siah’s rate of Ship’s Boy is a direct result of this policy, as the Navy quickly adopted a way enlist escaped slaves with useful skills, though the rate itself was the lowest in the Navy. The Act itself would not be officially repealed until 1864, though Union forces had stopped the returning altogether the year prior.

Not all slaves who made it to Union ships were granted the option to enlist, as one of the Monitor’s Engineers, George Geer wrote in June of 1862, “The conunterbands [sic] still come to us. While I am writing you we have two men and two women, all of them young, not over twenty two or three, in the Engine Room, drying their cloaths [sic] as it rains very hard. They came from a plantation some five miles up the river. As soon as it stops raining they will be put in their old boat and be sent away with the Captain’s advise [sic] to go home again…”

Siah would serve on the USS Monitor until her sinking in a heavy storm on December 31, 1862. The extremely low freeboard of the ship caused it to take on water while being towed during a heavy storm, eventually be breached, and almost drug the USS Rhode Island that was towing it down with her. Siah would go on to serve on five other vessels: the USS Brandywine, Florida, Belmont, Wabash, and Commodore Barney. At some point he must have re-enlisted because his rate was given a Landsmen aboard the Florida, which was the rate typical for new members of the Navy.

Siah would suffer a frostbite wound that would have him honorably discharged on May 19, 1865, just a day over three years of service. After the war he married Eliza Tarrow, a fellow slave from Shirley Plantation, and they settled down in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania to have thirteen children. He worked as a laborer within the city and would eventually pass away in 1892, being buried in Eden Cemetery.

Resources:

Find a Grave. Siah Hulett Carter. Accessed from https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/177015319/siah-hulett-carter.

Fleming, Hannah. “Meet (a few) Monitor Crew.” The Mariners’ Museum and Park. February 15, 2017. Accessed from https://blog.marinersmuseum.org/2017/02/meet-monitor-crew/.

Gibson, James F. James River, Va. Sailors on deck of U.S.S. Monitor; cookstove at left, July 9, 1862, photograph. Library of Congress, accessed on February 2, 2021 from https://www.loc.gov/resource/cwp.4a39562/.

Mosteller, Roy A. “Siah Carter.” The United States Navy Memorial. Accessed February 2, 2021 from https://navylog.navymemorial.org/carter-siah.

Reidy, Joseph P. “Black Men in the Navy Blue During the Civil War.” Prologue Magazine, Fall 2001, (33), 3. National Archives. Accessed from https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2001/fall/black-sailors-1.html.

The USS Monitor Center. “The Monitor’s Crew.” The Mariners’ Museum and Park. Accessed February 2, 2021 from https://monitorcenter.org/the-monitors-crew/.

Explore More Stories

USS Monitor: The First Union Ironclad