The “Ghost Army,” officially known as the 23rd Headquarters Special Troops, was a unique unit that played a crucial role in World War II. As the first mobile, multimedia, tactical deception unit in U.S. Army history, this group of 1,105 talented individuals comprised artists, engineers, professional soldiers, and draftees. Their primary mission was to create elaborate illusions that would deceive German forces and protect Allied troops. In honor of our latest exhibition, “Ghost Army: The Combat Con Artists of World War II,” explore more of their story.

The Origins and Formation of the Ghost Army

The unit’s formation was inspired by the success of British deception operations and the recognition that psychological warfare could be a powerful tool. Recruiting efforts focused on creative individuals from art schools, advertising agencies, and the entertainment industry, resulting in a diverse group of approximately 1,100 men.

Unconventional Warfare: The Ghost Army’s Unique Tactics

The 23rd’s capabilities were truly extraordinary. They could simulate the presence of two entire divisions, approximately 30,000 men, using a variety of ingenious tactics. These included deploying rubber inflatable tanks, trucks, and planes to create the appearance of a much larger force. The unit also excelled in generating false radio messages and realistic sound effects to further enhance their deceptions.

Key Operations and Missions of the Ghost Army

One of their most significant contributions was to Operation Fortitude, the massive deception campaign preceding D-Day. The Ghost Army created phantom divisions and false radio traffic to convince German forces that the invasion would occur at Pas-de-Calais rather than Normandy.

During the Battle of the Bulge, the unit’s deception tactics were instrumental in confusing German intelligence about Allied troop movements and strength. Their efforts helped buy valuable time for actual combat units to regroup and counter the German offensive.

The Ghost Army also played a vital role in the Allied crossing of the Rhine River. They simulated the presence of two entire divisions, drawing enemy attention away from the actual crossing points and ensuring a successful operation.

Throughout their service in the European Theater, the Ghost Army’s innovative use of inflatable tanks, sound effects, and false radio transmissions consistently fooled German forces, saving countless Allied lives and contributing significantly to the war effort.

Ghost Army Stories You Should Know

One of the most fascinating aspects of the Ghost Army was its composition. The unit included several individuals who would later become renowned artists, such as fashion designer Bill Blass, painter and sculptor Ellsworth Kelly, and photographer Art Kane. This concentration of creative talent contributed significantly to the unit’s success in crafting convincing battlefield illusions. Explore a few of their stories.

Theresa Ricard

A high school student during World War II, Teresa Ricard responded to a call put out by the 23rd Headquarters Special Troops to assist with the making of rubber inflatables. Ricard saw the call in a newspaper advertisement placed by the U.S. Rubber Company in Woonsocket, Rhode Island.

The advertisement called for help as it was soon to be engaged in producing the 93-pound inflatable tanks. Earning $.49 an hour after school, Ricard contributed to the Home Front war effort. This proved essential to Ghost Army strategies across the European Theater of Operations (ETO).

Lieutenant Colonel Ralph Ingersoll

Celebrity journalist and bestselling author Ralph Ingersoll worked as the managing editor of the “New Yorker,” publisher of “Fortune,” and founder of the New York newspaper called “PM.”

After joining the U.S. Army, Ingersoll teamed up with Colonel Billy Harris and, together with military planners in London, crafted the idea that led to the creation of the 23rd Headquarters Special Troops. Ingersoll often referred to the 23rd as “my con-artists” and claimed the unit’s creation was his sole original contribution to the war effort during World War II.

Colonel Hilton Howell Railey

New Orleans native Hilton Howell Railey first worked as a wartime correspondent, an investigative reporter, and also as the man responsible for recruiting Amelia Earhart to fly across the Atlantic Ocean.

During World War II, Railey became an officer in the U.S. Army and commanded the Army Experimental Station at Pine Camp in New York. He oversaw and was responsible for leading the sonic deception units, a subset of the 23rd Headquarters Special

Troops. After the war, Railey was awarded the Legion of Merit for his “outstanding leadership in the development of a project entirely new to the U.S. Army.”

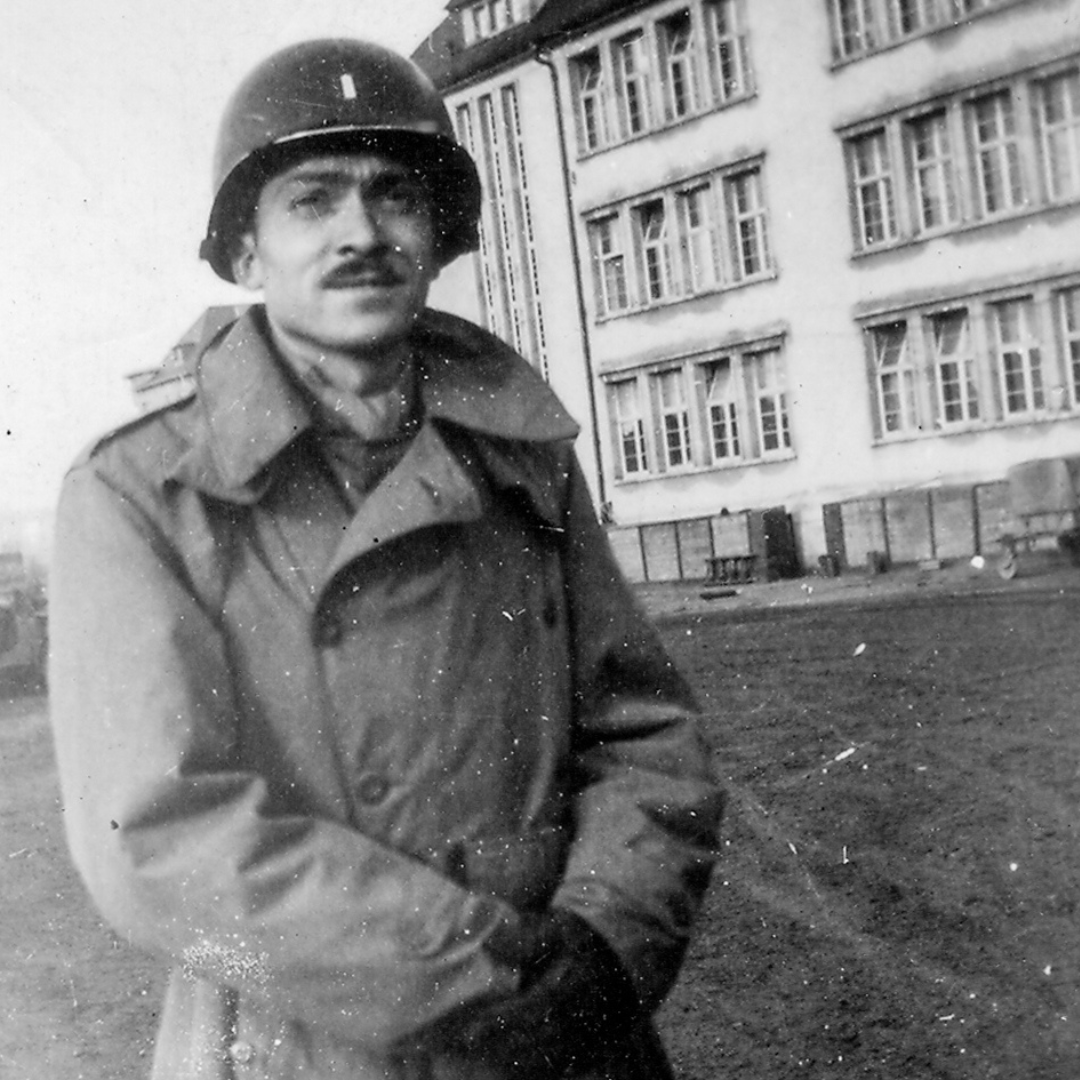

Lieutenant Dick Syracuse

Syracuse was transferred to the 3132nd where he trained in recording sounds to simulate large-scale construction projects, including the building of bridges, buildings, and tank movements to deceive the Germans into thinking that the Allies were constructing large structures. From that point, Syracuse became an important part of the sonic deception wing of the “Ghost Army”‘s tactics.

Private First Class Bill Blass

Born in Fort Wayne, Indiana, Bill Blass had an early interest in fashion design, and by the age of eighteen, he became the first man to win Mademoiselle’s Design for Living Award.

In 1943, Blass enlisted in the U.S. Army, and he ended up assigned to the 603rd Camouflage Battalion. Using his unique skills in fashion design, Blass created dummy tanks, inflatable planes and artillery pieces in order to deceive the Germans.

Following the end of World War II, Blass began his career in New York fashion and went on to become a household name. In 1967, Blass again offered his service to the military by designing the uniforms featured in the United States Pavilion guides for the 1967 World’s Fair in Montreal.

Learn more about their story:

The Ghost Army’s story is a testament to the power of creativity in warfare. Their unique blend of artistic talent and military strategy demonstrates how unconventional thinking can turn the tide of battle. As we delve deeper into their history, we gain a greater appreciation for the diverse skills and innovative approaches that contributed to the Allied victory in World War II.