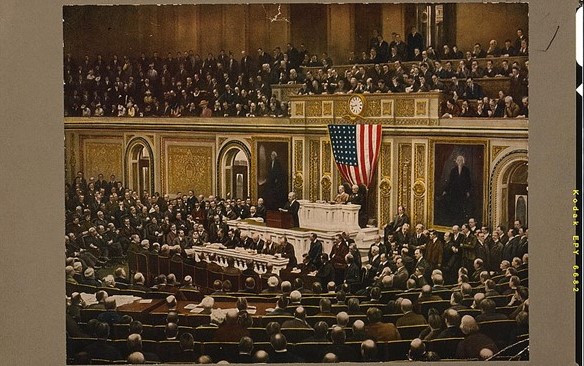

“Gentlemen of the Congress: I have called the Congress into extraordinary session because there are serious, very serious, choices of policy to be made, and made immediately, which it was neither right nor constitutionally permissible that I should assume the responsibility of making.”

This speech by President Woodrow Wilson on April 2nd to Congress would be put to vote two days later, and the United States would officially enter the war on April 6th. Germany’s use of unrestricted submarine warfare initially pushed the United States towards the Entente when 148 Americans died when HMS Lusitania was torpedoed, a violation of American rights as seen by those in the United States. But the scaling back of its use pacified U.S. entrance for the time being. The Zimmerman letter to Mexico, the move back to unrestricted submarine warfare by Germany, and Wilson’s want to shape the postwar world led to this special convening of Congress and the declaration of war against Germany.

To say the United States military was not ready for war on this scale would be an understatement. Within the Army alone, there was only a total of 308,771 troops between the Active Duty and National Guard components in a conflict that ended up averaging 6,000 casualties a day. The armies located in Europe numbered in the millions and were battle hardened after three years of bloody fighting. Vast and rapid mobilization was needed for the United States, with the first troops landing in Europe in June 1917.

It is very difficult to find veteran perspectives of this event. Indeed, what has been digitized seems to have a massive gap between January and September of 1917, with most of the letters that are available coming from those conscripted into the military. Those that have written about April do not mention the declaration of war, which could also have something to do with the passing of the Espionage Act of 1917.

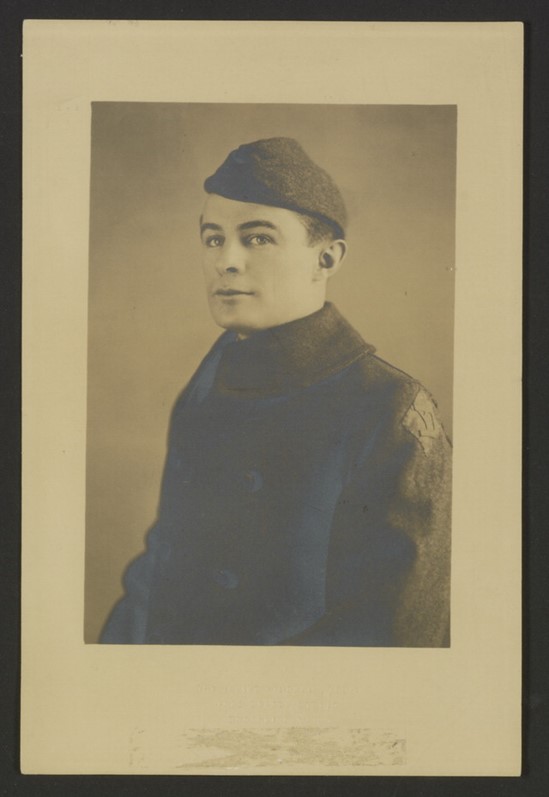

With that in mind, Corporal Edgar D. Andrews enlisted into the Army National Guard before the United States declared war, sometime either late 1916 or very early 1917, where he was placed into a machine gun battalion. His letters begin in January and seem to indicate a good sense of morale by Edgar and the others serving alongside him. There is a gap in correspondence between the end of January and October where his next available letter is about his safe arrival in France, with a note about the censors that will now be combing through their letters. Edgar would survive through the entirety of the US’s involvement in World War I, with a common theme in his letters being that family was his motivation to endure.

Resources

Edgar D. Andrews. Veterans History Project Collection, American Folklife Center, Library of Congress. Accessed from https://memory.loc.gov/diglib/vhp/story/loc.natlib.afc2001001.103623/.

Hirschfeld, Gerhard, Gerd Krumeich, and Irina Renz. Brill’s Encyclopedia of the First World War. Leiden, Boston: Brill. 2012.

Jackson, Galen. “The Offshore Balancing Thesis Reconsidered: Realism, the Balance of Power in Europe, and America’s Decision for War in 1917.” Security Studies, vol 21 (3). August 2012. doi: https://doi-org.ezproxy.lib.ou.edu/10.1080/09636412.2012.706502. Accessed from https://www-tandfonline-com.ezproxy.lib.ou.edu/doi/full/10.1080/09636412.2012.706502.

President Wilson’s Declaration of War Message to Congress, April 2, 1917; Records of the United States Senate; Record Group 46; National Archives. Accessed from https://www.archives.gov/historical-docs/todays-doc/?dod-date=402.

“U.S. Entry into World War I, 1917.” Office of the Historian. Accessed from https://history.state.gov/milestones/1914-1920/wwi#:~:text=On%20April%204%2C%201917%2C%20the,Hungary%20on%20December%207%2C%201917.