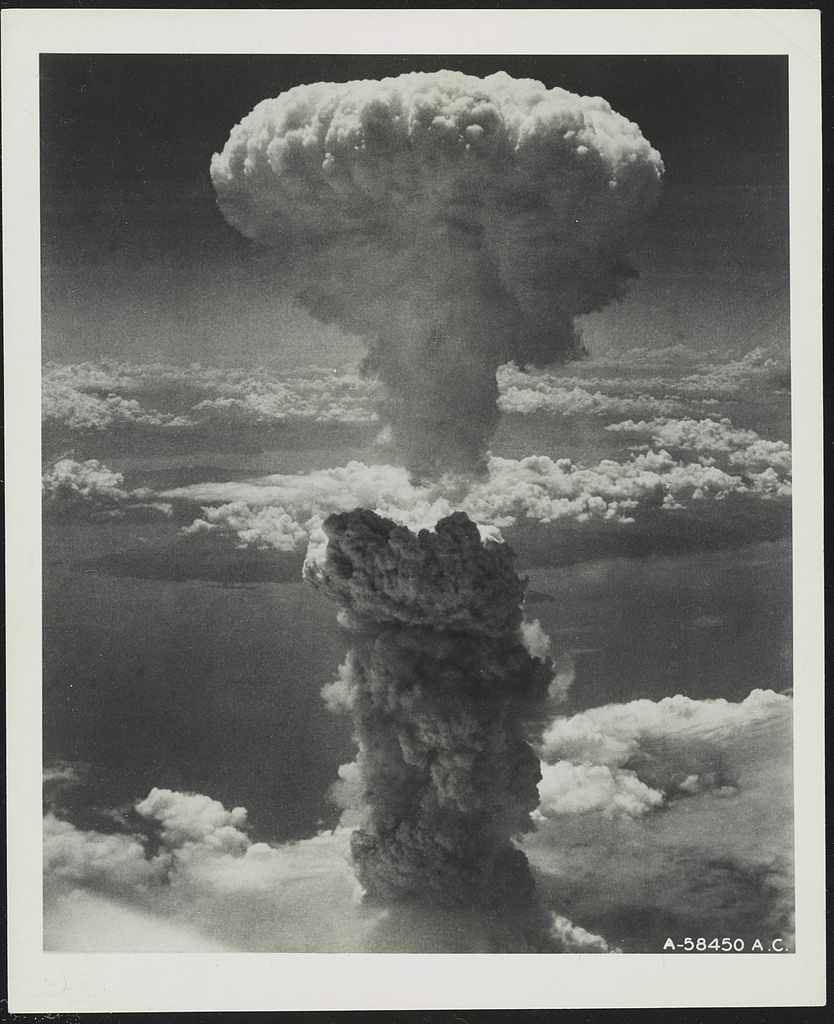

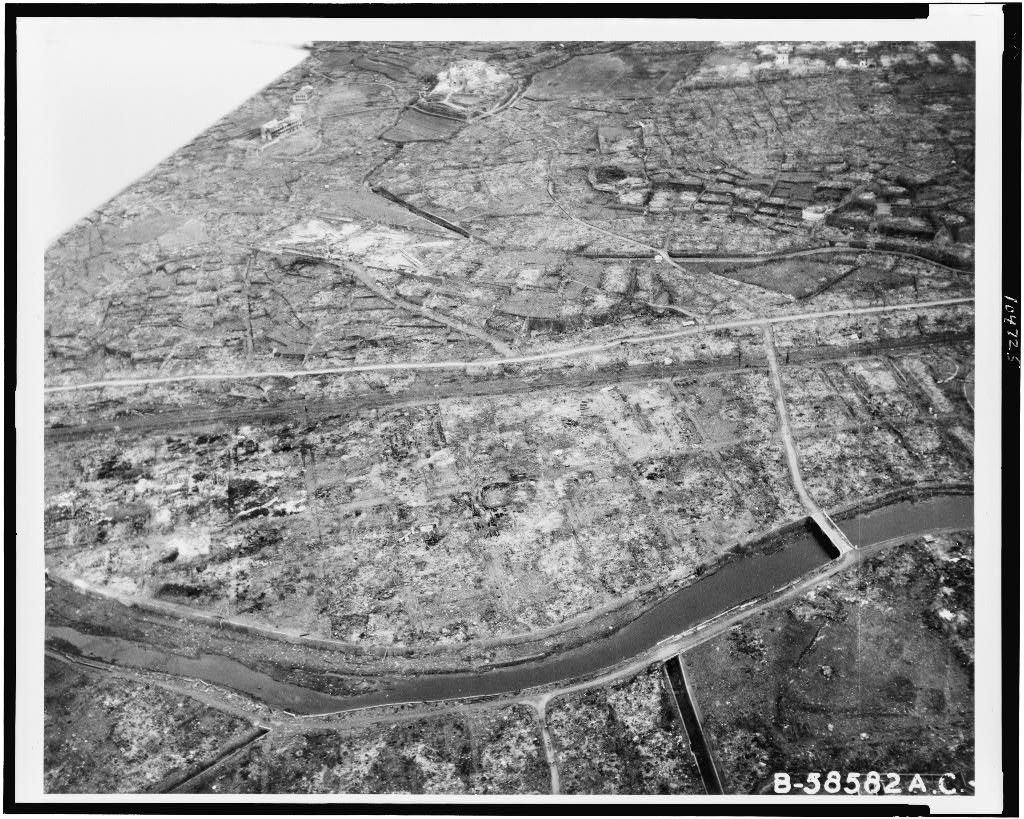

AUGUST 9, 1945

B-29 bomb dropped on Nagasaki, Japan

On May 7, 1945, Germany surrendered to the Allied powers ending World War II, but Japan refused to end the war in the Pacific. By 1944, the United States forces had gained control over most of the islands in the Pacific; they were now in perfect position to begin planning an invasion of Japan. However, the Japanese War Council refused to unconditionally surrender to the Allies. This led President Harry S. Truman to approve the dropping of two nuclear bombs created by the Manhattan Project on specific Japanese cities. The first bomb, “Little Boy,” was dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, killing 70,000 to 135,000 Japanese citizens. Despite the colossal loss of life, Japan did not surrender, leading to the dropping of a second bomb.

On August 9, 1945, the crew of the B-29 bomber, Bockscar, led by Maj. Charles W. Sweeney, started their mission to drop the second nuclear bomb, “Fat Man,” over Kokura, a city with several ordinance factories manufacturing chemical weapons. On that day, a thick cloud cover made it impossible to accurately target a location, which led Sweeney to change course and head to Nagasaki. At around 11 am, Sweeney gave the order to drop “Fat Man” over Nagasaki. An eyewitness account from William L. Laurence, a New York Times reporter aboard The Great Artiste, a Silverplate B-29 bomber, described the resulting explosion as a green flash of light that flooded the plain, followed by a plume of purple fire rising from the ground. Between 60,000 and 80,000 Nagasaki residents were killed by the 22-kiloton blast. Following the second bombing, on August 15, Japan’s Emperor Hirohito and the War Council unconditionally surrendered to the Allies.

While many have questioned the necessity of using nuclear bombs, the bravery of the men who flew those missions cannot be questioned. Today, let us remember the service members who did their duty and risked their lives to drop the second nuclear bomb over Nagasaki, as well as the Japanese civilians who lost their lives, families, and homes that day.

AUGUST 11, 2003

NATO assumes control of international peacekeeping efforts in Afghanistan

On August 11, 2003, German Lt. Gen. Norbert van Heyst handed the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) green flag to NATO Lt. Gen. Gotz Gliemeroth, symbolizing the passing of command in Afghanistan from Heyst to Gliemeroth. These two commanders met at Amani High School in the Afghan capital of Kabul where they conducted a formal ceremony to mark the historical moment. In 2003, NATO, which at that time had existed for 54 years, had yet to take part in a ground mission in a country that was not part of Europe. Despite the change in command, NATO was determined to maintain and fulfill the original mission of the International Security Assistance Force: to create a stable environment where the Afghan government and national security forces can maintain their control of the country.

This year marks the 18th anniversary of NATO taking command in Afghanistan. They have managed to fulfill their original mission, created the Resolute Support Mission (RSM) in 2015 to help Afghan’s security forces and established the Enduring Partnership with Afghanistan. While Allied forces began withdrawing from Afghanistan as of May 1, 2021, the partnership between NATO and Afghanistan remains strong.

Today, we honor the members of the International Security Assistance Force and recognize this historic moment in history.

AUGUST 12, 1952

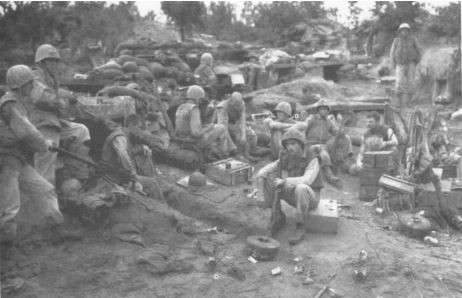

The 4-Day Battle of Bunker Hill begins

In 1952 during the Korean War, Marines were sent to the Jamestown Line, which was the U.N.’s main line of resistance across Korea. The Battle of Bunker Hill, also known as Hill 122, was critical because having possession of the Hill would enable a command to dominate Outpost Siberia and move beyond the PVA (Chinese Peoples Volunteer Army) Outpost line. The Marines fought to progress further onto Hill 122, and with the brilliant strategizing of Lt. Col. Gerard T. Armitage and Commanding Gen. John T. Selden, and others, the Marines continued to advance. After Bunker Hill was secured, the war continued onto the next outpost, Stromboli. Winning the Battle of Bunker Hill allowed the Marine’s significant advancement aiding in the armistice which ended the war.

AUGUST 13, 1918

Opha Mae Johnson enlisted in the United States Marine Corps

Opha May Johnson was 40 when she became the first woman ever sworn into the U.S. Marines Corps. Born in Kokomo, Indiana, on May 4, 1878, and raised in Washington, D.C., she graduated second in her class from Wood’s Commercial Business College. Before enlisting in the U.S. Marine Corps, she worked for 14 years in a civil service role at the Interstate Commerce Department. On August 13, 1918, Johnson happened to be at the front of the line with another 305 women who enlisted that day. Johnson was a clerk at the U.S. Marine Corps Headquarters in Arlington.

Today, we honor Opha and all of the brave women who followed her example by enlisting in the Marine Corp.

AUGUST 14

Navajo Code Talkers Day

Today, we honor and remember hundreds of Navajo Code Talkers and their significant contributions to the Allied victory in World War II. Throughout American history, Native American servicemen from more than twenty different tribes, including the Navajo, utilized their indigenous languages to assist in sending secret coded messages that our enemies could not brake or intercept. In 1942, 29 Navajo men were recruited and trained by the U.S. Marine Corps and worked to develop an undecipherable code that would be used across the Pacific during World War II. The “Code Talkers,” as they were called, became Platoon 382 – the first entirely Native American, all-Navajo platoon in U.S. Marine Corps history. Together, they generated more than 200 new Navajo words for U.S. military terms and committed them to memory in a timespan of several weeks.

Carl N. Gorman was one of the original Navajo Code Talkers who joined the Marine Corps in 1942 when he learned the military was recruiting Navajo speakers. In the 1996 book, “Power of a Navajo: Carl Gorman, the Man and His Life,” Pvt. 1st Class Gorman reflected on his experiences during World War II: “For us, everything is memory, it’s part of our heritage. We have no written language. Our songs, our prayers, our stories, they’re all handed down from grandfather to father to children—and we listen, we hear, we learn to remember everything. It’s part of our training.” After Gorman served in the battles of Guadalcanal, Tarawa, Tinian, and Saipan, he returned state-side and attended the Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles, California, on his GI Bill where he studied art. Throughout his life, he experimented with painting and other mediums including ceramics, tile, silk screening and jewelry design. Gorman created artwork for more than 50 years and combined his stories and experiences of childhood and Navajo life with a stylistically modernist-approach to his work.